Sorry, but I couldn’t resist spoofing, in the post title, the unfortunate sound of the acronym for the “new” model proposed in this article. Now, I’ve got it out of the way and can only suggest that if this “divergent fork of the Community of Inquiry model” is to survive, it needs a new English acronym.

This post is a critical review of Democratizing digital learning: theorizing the fully online learning community model Todd J. B. Blayone, Roland van Oostveen, Wendy Barber, Maurice DiGiuseppe and Elizabeth Childs. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2017 14:13

DOI: 10.1186/s41239-017-0051-4

First, let me get out the good things about this article stated. I love the fact that the authors published this in a peer reviewed, Open Access journal (thanks to Roland van Oostveen for noting an error in my original post) . Second I love articles about the now venerable Community of Inquiry model because it is flattering to see this work live on, nicely adds to our citation rating indices and because I share with Randy Garrison and Walter Archer an ongoing interest in constructivist models for online and blended education. And finally, as always conceptual arguments and calls for research are welcomed – especially if they follow with real research results!

First in a number of concerns with the paper. The basic claim is that the Fully Online Learning Community (FOLC) is a “divergent fork of the Community of Inquiry model”. It seems the divergent claim is made on the basis that the revision is for FULLY online courses. In fact no divergence is needed or called for as the original COI model was always based on fully online courses – blended courses – or at last the name hadn’t been invented in the 1990’s when we developed the COI model. The authors may argue that the divergence stems from the integration of synchronous and asynchronous discussions. The original COI model was grounded in asynchronous threaded discussion, as the Internet did not support synchronous interaction in those days. However, Randy and I had been working since 1989 on synchronous delivery models based on group teleconferencing, (see for example Anderson, T., & Garrison, D. R. (1995). Transactional issues in distance education: The impact of design in audio teleconferencing. American Journal of Distance Education, 9(2), 27-45.). We certainly thought the constructivist underpinnings of the COI could and would support synchronous communciations as well.

Second, is the claim that FOLC “responds to the limitations of distance learning and MOOCs (e.g., student isolation, low completion rates, etc.)” and “the needs of transformative and emancipatory learning” and “responds to requests from some international partners for new models of learning aligned with democratic and socio-economic reforms. Both Randy and I had long argued and published about the need for distance education to use technologies to get beyond distance education, as perceived as one-way content dissemination to “education at a distance” based on social construction. Thus, the ‘new’ FOLC adds nothing new to our initial claims and desire to supplant individualistic models of correspondence models of distance education. MOOCs and especially cMOOCs are much more than mere content dissemination as decried by these authors. Finally, the COI was and is a response to the need for new models of learning and the needs for emancipatory learning. The only claim that is true is that the COI didn’t directly respond to the need for 21st Century learning competencies -mostly because these hadn’t been invented when we developed the COI model. Moreover, these newer ideas certainly fit within the original COI and its development and support by thousands of researchers in the past two decades.

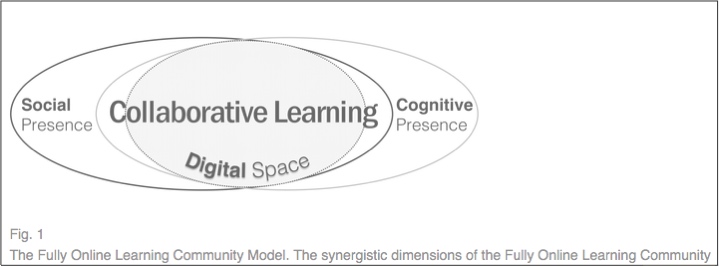

The authors present a “revised model” as below

I can’t see anything new here beyond the original three presence Venn diagram of the COI model. Both note the collaborative learning environment, both have social and cognitive presence and teaching presence is assumed in the organization and management of the digital space as the FOLC model (like the COI) is based on formal, institutionalized education.

The paper then goes on to provide conceptual scaffolding for a number of tending educational related theories or ideas – digital space; democratized learning and collective identity and responsibility, community and authenticity. I don’t have any problems with these conceptual arguments and they could each be used to update and strengthen the original COI model. I really don’t see anything new here except for the inclusion of references and arguments that have developed since the COI model was first introduced.

The article then goes onto to propose a research agenda which is little more than a wish list of things that could or should be researched. We criticized this type of rather adhoc model of research agenda development in our Stöter, J., Bullen, M., Zawacki-Richter, O., & von Prümmer, C. (2014). From the back door into the mainstream: The characteristics of lifelong learners. In O. Zawacki-Richter & T. Anderson (Eds.), Online distance education: Towards a research agenda (pp. 421-457). Athabasca: Athabasca University Press. But again, nothing wrong with this list of things to do, but nothing new either. Finally, the authors invite others to join them in this research process – all good stuff but….

I don’t think there is enough new here to claim a “divergent fork” merely by strengthening the original argument.

Terry, I’ve got a limited amount of time so I’m going to just note where I think there are significant, perhaps in matter of degree, differences between the original CoI Model and the derivative FOLC (we pronounce it FOLK) model. I’ve noted your initial insistence that there is nothing new in the FOLC model. By the end of your post, you do modify your stance to claim that you “don’t think there is enough new here”, signifying that there are some new ideas or perhaps variants and clarifications of the originals.

Semantics aside, perhaps you will allow me to emphasize a few ideas by quoting a few excerpts from a separate paper that is currently under review for publication in another international journal. The original conference paper upon which this new paper is based can be found at:

vanOostveen, R., DiGiuseppe, M., Barber, W., Blayone, T. & Childs, E. (2016). New conceptions for digital technology sandboxes: Developing a Fully Online Learning Communities (FOLC) model. In Proceedings of EdMedia: World Conference on Educational Media and Technology 2016 (pp. 672-680). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE), June 29, 2016, Vancouver, B.C.

Co-created Digital Learning Environment

Generally recognized as a framework for “facilitating deep and meaningful [collaborative-constructivist] learning in

a computer conference environment” (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000, p. 93), the Community of Inquiry (CoI)

framework identifies three presences essential to supporting distance education: Social Presence, Teaching Presence,

and Cognitive Presence. The FOLC model, however, is grounded in the General Technology Competency and Use

(GTCU) framework and considers that a technology object serves as an interface between the user and: 1) other

users, 2) stored information, and 3) information processing tools or software” (Desjardins, 2015). The GTCU

framework identifies four interrelated orders of technological competency, namely, the Technical, Social,

Informational, and Epistemological orders, which may be examined through use of the GTCU survey instrument.

Thus, the FOLC offers an alternative to CoI and related models (e.g., PLE, PLN) in that it is squarely situated within

the South-East quadrant of Coomey & Stephenson’s (2001) teaching-learning paradigm model. As such, the FOLC

requires the co-creation of the learning environment in a collaborative, constructivist manner.

As a process model with a specific control orientation, grounded on established praxis at a Canadian university, and

built upon strong constructivist foundations (Dewey, 1897, 1916, 1933; Piaget, 1959; Von Glasersfeld, 1989;

Vygotsky, 1978), it is important to distinguish FOLC from its generic cousin, the CoI (Garrison, 2011, 2013, 2016).

Several key distinctions are apparent. From a technology perspective, FOLC construes the digital space and enabling

technological abilities as integral to the online learning experience, not as indirect or exogenous variables (Garrison,

2011). Furthermore, from a communications modality perspective, FOLC does not recognize asynchronous, textbased

discussion as necessarily better serving the goals of collaborative inquiry (Garrison, 2013). Rather, it draws

attention to the evidence-based strengths of both synchronous and asynchronous technologies in relation to sociocultural

contexts and learning goals of particular online communities (Rockinson-Szapkiw, & Wendt, 2015).

Moreover, FOLC recognizes the profound strengths of synchronous video-conferencing technologies for allowing

members of an online community to experience community members as embodied human beings. This supports key

facets of the social presence (SP) aspect of the GTCU, including the building of mutual respect for the identity and

cultural differences among community members; the development of trust among community members; and the use

of emotionally rich and responsive communication via intonation, facial expression, and body language.

Shared Power/Control (contrasting with R. Garrison’s insistence on direct instruction)

Additionally, FOLC engenders a democratized and emancipatory control orientation, coupled with a constructivist,

epistemological perspective that varies with CoI. This has significant implications for FOLC’s operationalization of

teaching presence (TP) and cognitive presence (CP). With respect to TP, FOLC distributes leadership

responsibilities, and collapses facilitation dynamics into the broader functioning of social and cognitive presence

(Armellini & De Stefani, 2015). As described earlier, this implies that all members of a community share power,

control, and responsibility respecting the nature and direction of collaborative learning; including elements such as

selection of relevant information sources, choice of preferred digital devices and learning environments, negotiation

of outcomes, and participation in processes of assessment. Within this democratized context, the professional

educator, like a servant-leader, pursues the functional responsibility of empowerment (Parris & Peachey, 2013;

Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995; Zimmerman, 1995), and replaces directive communication with communication that

promotes mutual exploration, questioning, and challenge. With respect to CP, FOLC does not privilege any

particular model of inquiry. In fact, CoI bases its operational definition of cognitive presence on Dewey’s (1910)

practical inquiry model, considering it a generalization of “the scientific method” (Garrison, 2016, p. 76). Given that

the existence of a canonical “scientific method” is highly contested, in FOLC, the establishment of credibility

criteria for judging knowledge claims becomes a collaborative community endeavour. Consistent with this

epistemology, FOLC fosters cognitive development through individual knowledge construction and collaborative

discourse, rather than through the development of cognitive outcomes established by professional educators’

direction and control (Akyol & Garrison, 2014).

Use of PBL and Authentic Assessment

The provision of valid and reliable assessment and evaluation strategies are an essential part of fully online learning

communities. Authentic forms of assessments, in particular, have been discussed in digital contexts by numerous

authors (Herrington & Herrington, 2013; Reeves, Herrington, & Oliver, 2002; McNeill, Gosper, & Xu, 2012;

Herrington & Parker, 2013, Herrington, Parker, & Boase-Jelinek, 2012). FOLC’s use of real world tasks and ill

structured problems that have multiple solutions is central to the learning processes involved, and assessment

becomes seamlessly woven through the students’ tasks. Reeves, Herrington, and Oliver (2002) provide ten elements

that are required for authentic assessment activities, including that they have real world relevance; are ill defined

with multiple tasks and sub tasks; are complex and investigated over time; can be examined from different

perspectives; and provide the opportunity to collaborate. In addition, authentic tasks can be seamlessly integrated

with assessment; can be integrated across subject areas; provide opportunities for reflection and the creation of

polished products; and allow for diversity of outcomes (Reeves et al., 2002, p. 564).

Several authors identify the parameters for authentic learning environments and authentic assessment tasks. This

paper contextualizes these elements with reference particularly to synchronous online environments (Reeves,

Herrington, & Oliver, 2002; McCarthy, 2013; Rosemartin, 2013; Herrington & Herrington, 1998; Bozalek et al.,

2013). Literature reveals a general consensus about some of the key elements of an authentic learning environment.

These include:

Authentic context, authentic tasks, access to expert thinking and modelling of process, provision of

multiple roles and perspectives, collaborative construction of knowledge, reflection, articulation to

enable tacit knowledge to be made explicit, coaching and scaffolding, and authentic assessment of

learning within the tasks. (Bozalek et al., 2013, p. 631)

These aspects of assessment suit the 21st century context since today’s learners exist in a world that continually

redefines itself. The roles of teacher and learner are no longer defined in traditional ways, nor are they embedded

within traditional power structures. Thus, assessment can no longer reside solely in the hands of the instructor. In a

co-designed and co-created environment, assessment must be an ongoing process involving critical reflection and

ubiquitous consideration that is seamlessly woven into the learning process. Since the development of new

knowledge outpaces our ability to keep up with content, many authors have re-defined the essential skills required of

21st century learners. Several authors agree that these skills include the development of creativity, self-motivation,

innovation, problem-solving, and collaboration (McNeill, Gosper, & Xu, 2012; Voogt, Erstad, Dede, & Mishra,

2013; Kaufman, 2013). The formidable challenge for institutions is to work with learners to develop reliable means

of assessing these learning outcomes.

Operationalization of FOLCThe following description of the ESDT program is offered as an example of how the FOLC model can be

operationalized. Utilizing these principles in ESDT program courses, instructors, teaching assistants, and students

collaboratively function as co-creators of the learning environment—the digital space. Instructors begin the PBL

process by publishing YouTube videos as modified Problem Based Learning Objects (vanOostveen, Desjardins,

Bullock, DiGiuseppe, & Robertson, 2010). Students, in turn, use the YouTube videos to create ill-structured

problems. Students bring their thoughts and questions about these problems to the hour-long, facilitated audio-video

conferencing tutorial sessions. Acting initially as facilitators, instructors and teaching assistants (TAs) model a

process of eliciting preconceived notions about the problems from the students, and offering challenges to their

preconceptions (Bencze, 2008). Gradually, students wrest control of these interactions as they collaboratively learn

while investigating the problems and build toward solutions. Facilitation requires instructors and TAs to learn about

student cognitive understandings and emotional states, and then to act in ways that support and challenge the ideas

as they are presented. Students collaboratively make choices about problems and solutions, as well as the digital

tools they use while building their understanding of the problems and solutions. Periodically, students share their

work and critique the processes and conclusions that were reached within their own group and others. All members

of the community exhibit social and cognitive presence as they work at clarifying their problems and building their

solutions to those problems. Since students and facilitators take on similar roles, the FOLC model acts as a means of

reducing transactional distance (Moore, 1993) while simultaneously offering a way for students to move from visitor

to resident within the connected, networked web (Lave & Wenger, 1991; White & Cornu, 2011; Jones, 2015).

Admittedly, these may be nuanced differences between CoI and FOLC, however, when taken together, my colleagues and I determined that we were describing a variant of the original model. Even if the only changes present in the FOLC were conditions, technologies and affordances that were not available when the CoI was developed, wouldn’t this provide an argument for at least an update to the original model, a CoI v2.0 perhaps?

Hi Roland.

First a big thanks for taking the time and considerable effort to draft this scholarly response. I hope others will chime in or as Norm Vaughn suggested, continue this discussion on the new coi blog http://www.thecommunityofinquiry.org/

As you note my remark that there isn’t ANYTHING new was overstated. but as I note later I don’t think the added rationale provided by new technological and pedagogical developments warrants a “fork”.

As you note we didn’t have as much focus on the role of the media in the original papers. Although we certainly intuitively felt that the affordances of the Internet – even in nascent forms of text based conferencing, did create a new context for teaching and learning- and we (like many others) have tried to enhance and develop education with these affordances exploited.

The co-creation arguments I believe are consistent with (and subsist) in all three elements of the original model. Randy Garrison provides the following rationale and response to your comment.

“First, I am in complete agreement with Terry’s comments. To avoid sounding too defensive I will not rebut each argument. Roland makes my point when he states that “Admittedly, these may be nuanced differences between CoI and FOLC.” At best they are nuanced differences. My position is: why create confusion by introducing a difference that isn’t? At the heart is a lack of understanding of the true collaborative assumptions of the CoI. For example, each participant in a CoI is expected to assume all the responsibilities of teaching presence to various degrees – including direct instruction. This is not the sole responsibility of the instructor of record. Control can only be operationalized through a shared and collaborative dynamic. To understand this core assumption and dynamic I shamelessly recommend a deep reading of the latest version of E-learning in the 20th Century (2017). In conclusion, I suggest that what differences there are can easily be accommodated by refining and enriching the existing CoI framework.”

I would also argue that the “authentic” discourse is implicit in the creation of learning activities (teaching presence) if they are to be applied in the final stage of cognitive presence.

I think you have done a good job of showing how the model needs to grow and adapt to further evidence, but if the world of both academics and practitioners would be enhanced by a “fork” is left to the community itself. I have long argued that at least part of the continuing interest and use of the COI – is because of its simplicity. A number of authors have attempted to add a “fourth presence” to the model (I review some of these at http://virtualcanuck.ca/2016/01/04/a-fourth-presence-for-the-community-of-inquiry-model/ ) but none of these has become popular. As I note in that earlier blog, I like the notion by Peter Shea et al. for adding his ideas of ‘learning presence’ to make the COI a learning model as well as a teaching model, but despite this, the original COI model marches on through the literature and the minds of many practitioners

We shall see the fate of the FOAC model in the coming months and years.

Thanks again for your contribution.

Terry

Well – since Terry called me out by name here, thought I might jump in 😉 . I agree that the FOLC model does not appear to do a lot that is new. I had argued earlier that CoI was under articulated with regard to the distinct roles of teachers and learners and conflating those roles obfuscates as much as it illuminates. That is why I and my colleagues suggested that the teaching presence construct should acknowledge (at a minimum) that despite teachers and learners sharing roles related to assessment, it is clearly the instructors role and responsibility to actually assign formal grades.

This might seem a small issue, but given the social, economic, intellectual, and cultural importance of the actual credential (college degree) and the justifiable anxiety students feel in formal learning environments when confronted with the possibility that fellow students determine their very expensive and high stakes fate, a pragmatic stance would acknowledge that faculty have an obligation to “get assessment right”. Faculty have the authority of the institutional role in making high stakes assessments. Claiming that everyone does everything makes a muddle of important distinctions with regard to faculty.

On the other hand most contemporary accounts of learning also acknowledge that students have roles that are more specific to learners. In collaborative online environments this might include a recognition of the role of self and co-regulation of learning. We need to know more about what good online learners do as learners separate from what good instructors do. This includes planning, monitoring, reflecting, and adjusting strategies that promote individual and collective learning goals. And while Terry rightly states that the idea of online learning self- and co regulation (what we called learning presence) has not been as widely taken up as other constructs in the CoI literature, the primary article introducing the concept has been cited over 300 times. (https://scholar.google.com/scholar?oi=bibs&hl=en&cites=7516844029006896211).

In closing I agree we need to do more to develop a conceptual model specific to fully online environments. In part that requires that we figure out what problem we are trying to solve. It seems to me that while it’s nice to call everyone a teacher and everyone a learner, a lot gets lost in that framing. It may be even more productive to investigate the very real and pragmatic nature of online learners separate from online instructors.

Great chat.

I want to brief, but I think that Peter’s note implies a resolution to the tensions in this discussion. I think he is saying that the the CoL literature could be seen as inclusive of the FOLC literature in that the latter extends the thinking w/r/t fully online learning. And while Roland might well (probably will) argue that this diminishes the value of the FOLC’s contributions, I see it more as a refinement in a larger system that might include specific thinking about blended learning or an updated CSCL model, etc. I think the real value here lies in explaining the nuances and building a more complete understanding of human learning in general and online learning in particular.