I’ve just finished watching two films about, paid for and watched – with interest, by many Canadians.

The first film, TransCanada Summer takes the viewer across the country in 1958. Throughout the trip the film celebrates the industrialization and progress resulting from the construction of the Trans Canada Highway – the longest highway in the world at that time. The second film critically looks at these roads – first the railroads then the highways, from the perspective of the First Canadians – the aboriginal natives. These Canadians were largely ignored as these same roads brought to them an invasive of settlers, profiteers and religious evangelists.

I grew up in Calgary Alberta, which was then and is now the most “American” of Canadian cities. It was settled in large part by American ranchers and farmers moving north and west for “open spaces” By either luck or design, oil was first discovered and commercially exploited in Turner Valley south of Calgary. Soon networks with American oil companies made Calgary the centre of one the major oil producing regions in North America.

Given this personal culture history, I was not much prepared for my first summer in University when I lived 450 miles north of Calgary in the Northern bush. I was a member of the Alberta Service Corp, doing a Peace Core-type immersion in Cree Country. The community of Loon Lake Alberta had, two years before my arrival, first connected to the “colonial roads” built by government and oil money. Thus, these Cree peoples were coming to terms with easy access – both to and from their communities. Arriving were evangelical missionaries, mobile stores selling cheap trinkets and underwear and a host of new government officials in charge of everything from forests, to hospitals, to schools and to Indians. In the opposite direction, cars and taxi’s emerged from these formally isolated communities to allow a day or weekend shopping trip, booze run or an opportunity for the young people to explore beyond their traditional lands.

The first film, TransCanada Summer, by Ronald Dick (1958) is narrated by celebrated Canadian historian and broadcaster Pierre Burton. The film is a cross country road trip (with a few diversions) along the recently completed Trans Canada Highway. As in chronological stories, common in this type of North American film, the action starts in the east and proceeds West. The narrative commences with the hardy fishermen of Newfoundland building the first road across their province. It then travels across each province in turn, showing famous landmarks of mid 20 Century Canada – both natrual and human created. The narrative is decidedly pro “industrialization”. The word itself is used frequently to describe big and powerful buildings and machines with an occasional explosion as the highway is carved through mountains and over waterways. The narrator shows us giant smelters, industrial slag exiting blast furnaces and mighty shovels lifting and transporting.

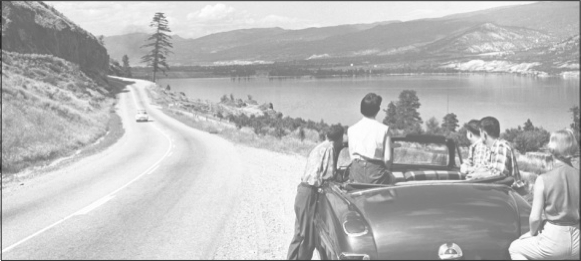

I confess that I really enjoyed the 60 minute video. Trans Canada Summer is the type of movie I would have enjoyed as a kid as my Jr High School teacher found a way to pass a Friday afternoon with bored students. Given that I was 8 years old when the film was made, I saw many of the scenes and especially the beautiful old cars I came to know (and own) as a teenager in Western Canada. The short hair cuts, long dresses and corny midway shows reminded me of the way life used to be. I also enjoyed identifying the famous landscapes – most of which I have had opportunity to visit in travels across the country.

Screen Shoot from Transcanada Summer

What was most shocking in this movie was the complete absence of any mention or footage of Canada’s First Nations – they were invisible across Canada. There was one very short shot of the famous French voyager and explorer Pierre La Vérendrye with a native at his feet pointing the direction – but that was it. No commentary of the critical roles played by the First Nations in the very survival of the earliest French and English settlements.

Sign on the Railroad bridge in Garden River Ontario. Shot from Transcanada Highway

There was no mention of the pivotal role played by First Nations people in not only supplying product, but transporting the fur trade throughout Rupert’s Land – the name given to Canada by its first commercial owners the Hudson’s Bay Company from London England. It seems as if the First Nations population was totally invisible in 1958 Canada. And of course there was no visits to First Nations communities despite the fact that the TransCanada passes through dozens of First Nations communities and reserves.

I recall that upon my return to university in Calgary, after my Service Corps summer, I was asked by a social worker if I would ‘befriend’ a First Nations student from the Blackfoot reserve near Calgary. It is almost unbelievable today, but he was one of only two registered Indian students in the whole University in 1970. So it perhaps no real surprise that First Nations were invisible, both to filmmakers and to the general population in the middle of the last century.

The second film, Colonization Road was shot in 2016 and tells quite a different story of the roads and railroads that “built” Canada. To set the context it is important to note that  Canada as a government and as a people are struggling to come to terms with its colonial history and most especially the past and current role of First Nations peoples in this history. A national attempt at reinterpretation and re-engagement was triggered by the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which researched, produced documents and held public meeting across Canada from 2008 to 2015. The TRC was officially struck to examine and reconcile with the tens of thousands of First Nation’s children who were legally abducted from the care of their parents and forced to live in mostly Church-run residential schools. The Commission brought to the public eye horrific stories of sexual, physical and cultural abuse as the missionaries attempted to take the Indian out of their young charges. Native language, clothing, spirituality, songs and attitudes were ruthlessly supplanted by Christian and capitalist ideas of correct behavior. These schools left a legacy of parents bringing up kids today who had never been properly parented themselves with resulting chaos and generations of suffering. The Commission ended in 2015 with a list of recommendations – some for governments but many for individuals and communities to begin the process of reconciliation based upon an accurate understanding of the truth of these first Canadians.

Canada as a government and as a people are struggling to come to terms with its colonial history and most especially the past and current role of First Nations peoples in this history. A national attempt at reinterpretation and re-engagement was triggered by the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which researched, produced documents and held public meeting across Canada from 2008 to 2015. The TRC was officially struck to examine and reconcile with the tens of thousands of First Nation’s children who were legally abducted from the care of their parents and forced to live in mostly Church-run residential schools. The Commission brought to the public eye horrific stories of sexual, physical and cultural abuse as the missionaries attempted to take the Indian out of their young charges. Native language, clothing, spirituality, songs and attitudes were ruthlessly supplanted by Christian and capitalist ideas of correct behavior. These schools left a legacy of parents bringing up kids today who had never been properly parented themselves with resulting chaos and generations of suffering. The Commission ended in 2015 with a list of recommendations – some for governments but many for individuals and communities to begin the process of reconciliation based upon an accurate understanding of the truth of these first Canadians.

The second contextual factor to set the current Canadian scene is the huge increase in First Nations populations from around 200,000 in 1960 to around 1,600,000 in 2016 . Thus, both increase of knowledge of our colonial past plus rapidly increasing populations are forcing Canadians to come to know, appreciate and work together with these first citizens of Canada.

In Colonization Road comedian and narrator Ryan McMahon visits some of communities across Ontario where they still have roads named Colonization Road. Governments of the day thought that if they pushed a road through the ‘empty wilderness’ then immigrant settlers would take the opportunity to buy cheap land, create villages and towns, build churches and schools and civilize the extensive Canadian bush. In total over 160,000 km of Colonization roads were built across mostly Northern Ontario land in the 1850’s. And it largely worked. Except they forgot one thing – the ‘empty’ land was already occupied by First Nations peoples living sometimes on smaller reserves but always using the land as traditional hunting grounds. Michelle St. John, director of Colonization Road writes “I think we’ve all been raised here in Canada with the settler narrative as one of triumph and a patriotic Canadian identity, but there is a flip-side to that story — and that story is ongoing.”

From the perspective of many of those interviewed the Colonization Roads were the conduit for not only white farmers, but for miners, loggers, gamblers and missionaries to enter and quickly usurp their land. This same strategy was used by later governments in Western Canada but then using the railroad to colonize and civilize Western Canada. Colonization Road visits communities that and more importantly tells the stories and reactions to First Nations citizens today and the stories from their parents about live both before and after colonization – and much of it is not pretty.

Both of these movies are worth watching – TransCanada Summer for a look at the natural beauty, the value of mid-century white Canadians and the narrative that both sets and reflects the noninvolvement of Canada’s First Nations in the economic development of the country then and continuing today. Colonization Road is both funny (thanks to First Nations comedian Ryan McMahon) and inspiring, as it gives voice to some of those people who experienced and suffered from the colonization of our great country.

The complete version of TransCanada Summer can be streamed

Here is the 2 minute trailer from Colonization Road.

Colonization Road Trailer from Frog Girl Films on Vimeo.