I’m not immune from the relentless hype (and warnings from multiple perspectives) about generalized AI, AI enhanced browsers and AI customized for specific applications.

Therefore, I couldn’t resist spending a few minutes checking out an AI app – Answerthis.io specifically aimed at researchers and students – see https://answerthis.io/

Not being overly modest (to say the least) I decided to ask a question about an idea that I had and paper I wrote over 20 years ago (Anderson, T. (2003). Getting the mix right again: An updated and theoretical rationale for interaction – International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 4(2).

The paper achieved modest success (1100 citations) which was a bit surprising as I wasn’t really sure there really was a learning equivalency between content interaction; student/teacher interaction; and student-student interaction. Moreover, I wasn’t sure how this ‘theory’ could be empirically validated nor disproved. However, over the years a number of researchers (aided in no small part by my Japanese colleague Terumi Miyazoke) have used it and seems to have been useful – perhaps most noticeably for financially pressed distance education administrators trying to create affordable (and thus accessible) learning opportunities.

So I asked Answerthis.io “What is useful about Anderson’s Interaction equivalency theory?”

It examined 93 papers in a minute or two and came back with more indicators of usefulness than I could remember. The resulting “answer” is as follows:

______________________________________________________________

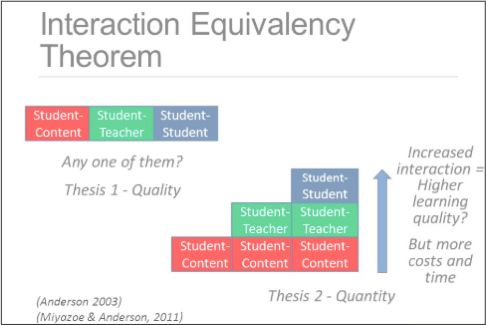

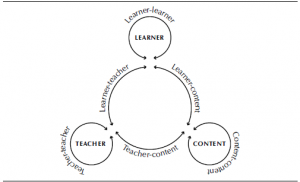

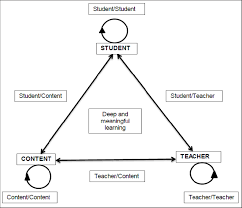

“Anderson’s Interaction Equivalency Theory” (also known as the Interaction Equivalency Theorem, or EQuiv) is a significant conceptual framework in online and distance education. At its core, it states that “deep and meaningful learning is supported as long as one of three forms of interaction (student-teacher, student-student, student-content) is at a high level; the other two may be offered at minimal levels or even eliminated without degrading the educational experience.” The theory recognizes that sustaining all forms of interaction at maximum levels may not always be feasible due to constraints such as time, resources, and institutional scale, especially in online or blended environments.

Key Benefits and Usefulness of Anderson’s Theory

-

Flexible Course Design and Resource Allocation:

EQuiv allows educational designers and institutions to focus resources and instructional efforts where they are most impactful. If strong interaction can be established in one domain (e.g., through rich content or peer collaboration), then the other types may be comparatively minimized without a loss in learning quality. For instance, in very large courses where teacher-student interactions are limited, enhanced student-content or student-student interactions can compensate, enabling scalability without compromising outcomes[1]. -

Personalization and Adaptation:

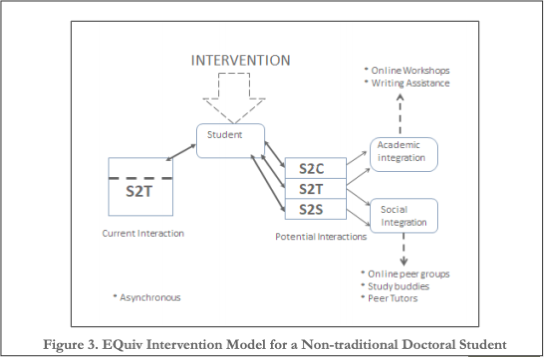

The theory provides a rationale to adapt interaction according to the specific needs and circumstances of different learner groups, such as non-traditional or part-time students who may not engage frequently with instructors but can benefit from alternative interaction forms[2]. -

Practical Framework for Blended and Online Learning:

It offers educators a guide to make informed decisions on which instructional tools or approaches to use, justifying, for instance, the use of Learning Management Systems (LMS) to enhance interaction and accessibility, allowing for key educational goals (like participation and learning engagement) to be met even if instructor interaction is limited[1]. -

Supports Student Satisfaction and Achievement:

Empirical and conceptual studies support the application of EQuiv in raising learner satisfaction, reducing attrition risk in distance education settings, and increasing course completion rates particularly when strong “interaction presence” is maintained in at least one channel[2]. -

Guides Risk Identification and Intervention:

The theory isn’t just for course designers—it can be used by institutions to develop risk profiles of students potentially at risk of dropping out, enabling targeted interventions where interaction is lacking[2]. -

Extends Beyond Structured Courses:

Although EQuiv originated in distance and online learning, it has potential applications in other higher education contexts, such as the master-apprentice model in doctoral education. By compensating for limited supervisor (S2T) interaction with enhanced content or peer interactions, EQuiv addresses issues of isolation and supports deeper learning[2]. -

Efficient Use of Learning Technologies:

By focusing on maximizing one type of interaction, it provides a rationale for the use of asynchronous content, peer forums, or automated feedback systems—tools essential for scaling and accessibility in digital education[1]. -

Framework for Ongoing Research and Development:

The theory has stimulated further research into interaction dynamics, informing both empirical investigations and theoretical development around how different forms of interaction contribute to learning, motivation, and retention in virtual environments[1], [2]. -

Facilitates Deep and Meaningful Learning:

The focus on ensuring at least one robust interaction provides conceptual and empirical support for deep cognitive engagement, even when all three modes are not maximally present. This is crucial for the design of effective massive open online courses (MOOCs) and large-scale distance education where teacher-student contact is inherently limited. -

Guides Implementation of New Educational Models:

EQuiv justifies the structural design decisions in “flipped classrooms,” blended courses, and synchronous/asynchronous online programs, providing a theoretical foundation for deliberate reduction or enhancement of interaction modes based on course goals, audience, and technological affordances[1].

In summary, Anderson’s Interaction Equivalency Theory is useful because it offers a flexible, evidence-based, and scalable framework for online, blended, and distance education. By clarifying how and where to invest instructional resources, it enables educators and institutions to optimize learning outcomes, enhance satisfaction, reduce attrition, and adapt to diverse learner needs across multiple educational contexts[1], [2“

__________________________________________

My takeaways:

- The tool does a credible and amazingly thorough job that seems quite accurate.

- It shows that assigning tasks such as this as an assessment activity in a senior undergrad or grad course hardly seems worth either keep student learning nor the time and effort taken by a teacher trying to assess it. I have had graduate students create blog and wiki entries on major ideas in distance education in the past, but given these tools, think it is an exercise in continuously “reinventing the wheel”.

- For a busy scholar (or student) trying to get up to speed on ideas from the literature that they may have missed or need a refresher, the tool is remarkably both efficient and effective.

- The tool doesn’t yet have much of a revenue model- but no doubt that will come.