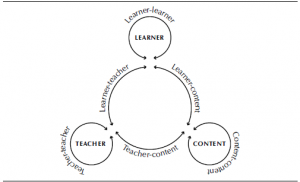

I’ve been fascinated by the role of interaction all of my career as both a student, a researcher and a teacher. Michael Moore’s famous article details the role of the ‘big three’ (student-student, student-content, student-teacher) interactions and influenced Randy Garrison and I to explore the other 3 possibilities (teacher-teacher, teacher-content and content-content interactions). I’ve written a number of summary articles, a recent article on interaction in MOOCs and note that interaction serves as the primary indicator of ‘presence’ in the Community of Inquiry (COI) Model.

Many, many research articles have shown significant and positive relationships between interaction and a host of outcomes including persistence, achievement and enjoyment. However, these studies are almost always correlational and sometimes based exclusively on student perceptions. These are useful methodologies but marred by challenges of proving causation. Did the interaction cause the positive outcomes (causation) or do motivated students both interact more and get better marks (correlation)?

Thus, I was pleased to see an interaction study in the latest issue of IRRODL that used a quasi-experimental study to examine the impact of student-teacher interaction. The article:

Cho, M., & Tobias, S. (2016). Should Instructors Require Discussion in Online Courses? Effects of Online Discussion on Community of Inquiry, Learner Time, Satisfaction, and Achievement. The International Review Of Research In Open And Distributed Learning, 17(2). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i2.2342

The study was set in the context of a US undergraduate, fully online course with between 25-30 students in each of three sections taught by the same instructor. In the first instance there was no discussion. In the 2nd, the teacher posted a weekly discussion question and students were obliged to post at least one answer and one comment per week (typical forced participation that brought down the wrath of friend Jon Dron in a recent post). In the final section the teacher actively participated in the weekly discussions. In all cases the teacher was readily accessible via email.

A strength of the study was the multiple measures of interaction effects. These included:

- completion of the COI Inventory – a Likert-scale, perception instrument derived from the original indicators of teaching, social and cognitive presence).

- Student satisfaction measured by 3 lLkert questions

- Time on task as represented by login time to the LMS

- Student achievement as measured by final grade. The authors wisely excluded the marks for participation awarded in instance2 and 3.

Perhaps the least surprising outcome was that perceptions of social presence were significantly different with, as expected, higher perceptions of social presence in the more interactive instances. Also not surprising is that teaching presence increased in the 3rd instance, but not significantly.

The results became both interesting and surprising on the final 3 measures. In each of the three course sections, each with markedly different amounts of interaction, there were NO significant differences in terms of time on task (logged into Blackboard), student satisfaction or student achievement. There was a small (but not significant ) increase in student satisfaction in the 3rd instance with enhanced teacher participation.

The discussion section of this paper is also very good. They note that time requirements for participation required in the forums in instances 2 and 3 did not end up costing students more time – at least as measured by Blackboard logins. Finally, they note the obvious – teacher participation did not lead to increased achievement – despite the assumed time commitment required of the teacher.

These results tend to reduce support for the importance a number of the types of student and teaching presence described and promoted in the COI model. But the results provide support for the ideas I promoted in my Interaction Equivalency Theory. I proposed there that given high levels of one of the three levels of interaction, the other two could be reduced without loss of academic achievement. I also noted in my 2nd thesis of that work that likely increased satisfaction would results if more than one of the three forms were used (in this study, there was an increase but it was not significant in student satisfaction across the instances) but that it would come at increased cost (usually time to both teachers and students).

The study also did not look at attrition, perhaps because the numbers were small. I know from experience at Athabasca, when teaching and peer interaction is drastically reduced in self paced and continuous enrolment designs, that attrition almost always increases.

This excellent study concludes with recommendations for practice which include the note that student-student and student-teacher interaction are just choices and shouldn’t be considered to be hallmarks of all online (or classroom) courses. Good learning design counts!