The Community of Inquiry has emerged as the most widely referenced (the seminal 1999 article approaches 3,000 citations) and arguably the most widely used model for constructivist based e-learning design and research. I’ve always thought that it’s greatest strength is its simplicity (only 3 major, but interacting components) and the way the model can readily be used by teachers to devise and evaluate online learning courses and by researchers to guide the development of research questions and data collection strategies.

In the late 90’s we were interested in showing empirically that emerging ‘new’ forms of interactive distance education could support the type of high quality learning that is possible (though certainly not always available) in classrooms. We wanted to provide evidence for Randy Garrison’s claim that this was a new mode of teaching and learning that was education at a distance – not high tech, traditional cognitive behavioural style distance education. Thus, we focused on a key component of constructivist learning –social presence. We also picked up on Randy’s earlier work (based on Ennes, Paul and Lipman’s work) on critical thinking to devise the phases of cognitive presence. Finally, though Walter Archer, Randy and myself were all active in informal adult learning, we realized that the activity we were focusing on took place in institutional contexts with students studying in degree programs. Thus, we wanted a focus on the critical design, facilitation and subject matter expertise components of teaching presence.

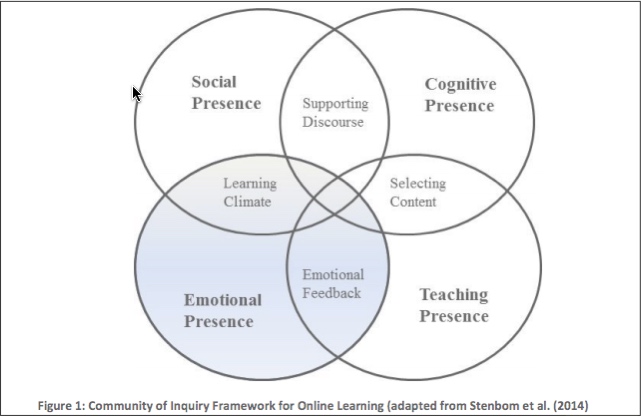

Perhaps we quit too early, as this post argues next, but we had created a parsimonious model that was easily illustrated in the now famous COI Venn diagram. I also recall the fluidity with which new indicators were added to each of the presences as we poured over the transcripts from asynchronous computer conference based courses. In early days, it was easy to add, delete or reword indicators, but the three presences seemed to us then to account for all the major themes of successful online courses. A special call out here to Liam Rourke who worked as a graduate student on this project, and was responsible for much of this early identification and classification work. The COI work was especially enhanced with the development by Ben Arbaugh and colleagues of the COI survey, which made it much easier to gather perception data to measure each of the three presences.

We have never argued that the model identifies all possible components of successful formal education – either online or in the classroom. And perhaps not surprisingly, it wasn’t long before additions (and a few deletions) were suggested. For example, David Annand, (2011) suggested that social presence wasn’t really needed for effective teaching and learning.

A number of researchers picked up on the need for the contextual or interface “presence” and in the case of distance education for the participants to master the mediating technology. Gilly Salmon (2000) in her famous 7 step e-learning moderation model sees such technical support as a key component of each of her moderation steps. I was never that impressed with these arguments as every context – including classrooms, uses some combination of asynchronous and synchronous media to support teaching and learning. Thus, the “presence” of the media and the need for and skill with which teachers and learners adapt to it is a minor factor that is unique to each teaching and context and I thought would needlessly complicate the COI model.

First came the close to convincing arguments from Peter Shea and his colleagues that the COI model lacked awareness of the critical role that the learner plays in formal education. We all realize that the same learning context and interventions can affect different students with vastly different effect. Thus, Shea and Bidjerano (2010) postulated the need for Learner Presence to account for these important learner set of variables in either online or classroom education.

Marti Cleveland-Innes, Prisca Campbell (2012) and other of Marti’s colleagues next argued that “emotional presence” was notably absent from the original COI model. My rather lame excuse that 3 males from Alberta, were very unlikely to posit the existence of emotional presence, since “real men” in Alberta, don’t do ‘emotion’. Rienties and Rivers (2014) picked up on these ideas of emotional presence in a review study – Measuring and Understanding Learner Emotions: Evidence and Prospects. They who directly added a fourth element to create what technically is now no longer a Venn diagram since it does not show all possible interactions of all 4 components. It is now a Euler model – see http://math.stackexchange.com/questions/1475/why-can-a-venn-diagram-for-4-sets-not-be-constructed-using-circles).

The most recent suggestion for a fourth presence comes from Lam (2015) who validated the existence of the original three presences, and then coined a new term for the type of learner agency that resonates with Shea’s “learning presence. Unfortunately she described this new addition to the COI as “Autonomy Presence”. Wikipedia explains that Autonomy comes from Ancient Greek: αὐτονομία autonomia from αὐτόνομος autonomos from αὐτο- auto- “self” and νόμος nomos, “law”, hence when combined, is understood to mean “one who gives oneself one’s own law” (Wikipedia). The word is used largely in the context of independence and freedom to make one’s own decisions. In educational context, this “autonomy” is valued to some degree, but as all students know, is severely curtailed by the edicts and wishes of the teacher. The indicators that Lam uses to identify and classify autonomy presence are however becoming increasingly important as the Internet provides additional or supplemental resources and communities that students can use to enhance, augment and validate their learning. (see below)

Terumi Miyazoe and I (2015) discussed this empowerment and the ability for students to increase student-student and student-content interaction in the context of my interaction equivalency theory in our 2015 paper Interaction Equivalency in the OER and Informal Learning Era.

It strikes me that the critical elements of learner, interface and autonomous presence flow directly from Alberta Bandura’s (1989) work on agency in which he described three types of agency in social cognitive theory. These are autonomous, mechanical and emergent interactive agency (p. 1175). The word agency evolved from Medieval Latin agentia “active operation,” Certainly the capacity for “active operation” can include most of the elements of interface presence since being productively active implies control over the environment. Shea’s reminder of the importance of the learning presence in the control of “active operation” is also subsumed in agency.

So my own suggestion in the search for the ‘missing’ element(s) in the COI model is to add agency presence to the COI trinity. This term is simpler than autonomous, builds on the seminal work of Bandura and captures the components mentioned by both Shea and Lam.

But where does that leave emotional presence? I argue that emotion is included in social presence (for example the indicator use of affective language) elements and in agency presence in line with both Bandura’s autonomous interaction – the capacity to recognize and use the power, insights and liability of emotional responses and his emergent agency in which emotions can be used to reach insights not accessible to those denying their existence or unable to deal with them effectively.

I haven’t validated this model empirically but it would likely include and consolidate many of the elements identified by Lam in her autonomous presence and Shea in his learning presence. And hopefully this addition would bring the COI model more in line with the emergent and networked resource ideas of modern connectivist theories.

References

Annand, D. (2011). Social presence within the community of inquiry framework. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(5), 40-56.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American psychologist, 44(9), 1175.

Cleveland-Innes, M., & Campbell, P. (2012). Emotional presence, learning, and the online learning environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(4), 269-292.

Lam, J. (2015). Autonomy presence in the extended community of inquiry International Journal of Continuing Education and Lifelong Learning, 81(1), 39-61.

Miyazoe, T., & Anderson, T. (2015). Interaction equivalency in an OER, MOOC and informal learning era. Best of Eden 2013 Issue – EURODL. http://www.eurodl.org/?p=special&sp=articles&inum=7&article=695.

Rienties, B., & Rivers, B. A. (2014). Measuring and understanding learner emotions: Evidence and prospects. Learning Analytics Community Exchange.

Salmon, G. (2000). E-moderating: The key to teaching and learning online. London: Kogan Page.

Shea, P., & Bidjerano, T. (2010). Learning presence: Towards a theory of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and the development of a communities of inquiry in online and blended learning environments. Computers & Education, 55(4), 1721-1731.

I find social science jargon impenetrable. Which is unfortunate, as this post sounds very relevant to an essay I m writing on What role technology enhanced learning has to play in helping disinterested or ambivalent clinicians opt into clinical teaching.( there is no finiancial or other incentives and lots of disincentives) I m no luddite and use technology enhanced learning with my undergrads. But the clinician population is much more complex (because of their ambivalence). I would like to map that complexity using your model, but I don’t understand it.

I’m not a fan of adding a fourth presence and certainly wouldn’t advocate for independent agency in a model created to illuminate community. Each actor in the community, who at any given moment may act in the role of learner, teacher, or both, should act as a community member.

I must protest your maintaining the notion that emotional presence only resides with social presence. Yikes! We’ve tested this multiple times now and emotion spans the model, and emerges separately in component analysis. I’ll send references later today. The relationship between cognition and emotion is well-established now that brain science has advanced dramatically since the CoI model was created. And to teach without awareness of emotion as a intractable characteristic of the human experience is to minimize the learning and community experience! Who doesn’t love, for example, a teacher passionate about the subject matter!

Quoted from an email from Randy Garrison on the topic:

I love the line re the “search for the ‘missing’ element(s) in the COI” framework.

Perhaps not surprisingly I am not convinced we are missing a new element. I think it is a matter of refining the existing elements and assigning other major agents to the broader contextual influences we have labeled exogenous variables (eg, technology, subject matter, student level/abilities). Keep in mind that the three presences only reflect the core educational experience.

Unfortunately what is being violated without the full recognition of its importance and loss is parsimony. Trying to make sense of all interactions of four elements is beyond my mental abilities and I suspect most practitioners. In other words, it would lose tremendous practical value to expand its comprehensiveness. As noted, my position is that the theoretical range could be expanded through a refinement of the individual elements without distorting the core structure.

For example, while emotional presence may be first identified within social presence (socio-emotional), SP and therefore emotion intersects with the other elements (presences intersect and are therefore interdependent). Emotion is therefore inherently pervasive as conceptualized. I agree with Marti in terms of its importance and influence but I believe we simply need to emphasize its “expanded role.” I am currently working on a third edition of the E-learning in HE book and discuss this as follows:

“… there is no question as to the intimate connection emotion has to all aspects of a community of inquiry. It could be argued that emotion is the gravity of a community of inquiry in that it is pervasive and acts differentially on all the presences depending on contextual conditions. The influence of emotion and how it fits in the CoI framework needs to be explored and understood. The question is whether it is helpful to see emotion as emanating from social presence or as a distinct generalized environmental influence …”

As I understand the other suggestions for a fourth presence, they violate the basic premise of the CoI framework in terms of participants being both teachers and learners and therefore the interdependence of the elements. In essence what is being suggested is a new framework; it would no longer be the CoI theoretical framework and should be indicated as such.

I remain convinced that the issues can be incorporated within the current CoI structure but continue to read such suggestions with great interest as it helps me refine and better understand the CoI theoretical framework.

R

D. Randy Garrison

Professor Emeritus

University of Calgary

Thank you Randy – this adds much grounding to the developing complexity that results from continued exploration and application of the CoI conceptual framework.

To your point, the overlap among the presences, currently known as supporting discourse, selecting content, and creating climate, could definitely use more illumination.

Perhaps through this work on overlapping presences, emotion’s role, among other influences, could be further described. The topic of emotion and online learning is getting increasing press, including a recent special issue of the Internet and Higher Education: Emotions in online learning environments: Introduction to the special issue (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1096751612000243).

As well, this interesting discussion has just emerged:

Chanel, G., Lalanne, D., Lavoué, E., Lund, K., Molinari, G., Ringeval, F., & Weinberger, A. (2016). Grand Challenge Problem 2: Adaptive awareness for social regulation of emotions in online collaborative learning environments. In Grand Challenge Problems in Technology-Enhanced Learning II: MOOCs and Beyond (pp. 13-16). Springer International Publishing.

Thank you for this informative post. Agency is my #oneword for this year. I’m literally in the shadow of giants…

In my masters program I’ve focused presence in online instruction to meet the unique professional learning needs of teachers. My model has 6 presences: Instructor, Social Media, Community, Cognitive, MetaTeaching and Design presence surrounded by and grounded in UDL principles. I, with two colleagues Dr. Elizabeth Dalton and Dr. Luis Pérez, created a SOOC (Small, Short, Supported & Social Open Online Course) on UDL & Apps for educators. The course design and delivery informed my model. The course also included co-construction with the instructor as participant which isn’t reflected in the model.

One presence that I think fits with CoI is Design Presence. Beyond instructional design (although related) it supports LX and is a combination of accessibility, technical production and aesthetics that support learner variability and reduce friction for online learners.

In addition, divided social presence into social media presence and community to reflect the huge changes in connectivity since the model’s inception and to recognize professional growth within a community of practice focused on problems related to professional practice. SM acts as a platform, a profile and an instructional strategy.

The other presence, unique to teachers is Metateaching presence. It pulls reflection out of cognitive presence to emphasize it’s importance if we are to see a change in instructional practice. It is part of an inquiry model and interconnects with community presence.

Wilkoff (2015) notes the goal of all professional learning is to create a change in practice, commenting that self-reflection is key. However, “…research indicates that teachers tend to use reflection in a descriptive, technical way by looking at what happened, without critical consideration of why or considering its implications.” (Kohen & Kramarski, 2012).

Teachers have unique learning needs (Grant, 2013). To embrace change, teachers need to reflect on their experiences as a learner and then step back and examine the same experience as a teacher, in a process referred to as metateaching. Metateaching asks teachers to expand their view. To consider not just what they learned or what did or didn’t work for them as a learner, but what the activity told them about learners in general and their teaching in particular. (Timpson, 1999)

FWIW

Kendra

Kohen, Z., & Kramarski, B. (2012). Developing self-regulation by using reflective support in a video-digital microteaching environment. Education Research International, 1-10. doi:10.1155/2012/105246

Timpson, W. M. (1999). Metateaching and the instructional map. Madison, WI: Atwood Pub.

Interesting addition! In my version “of expanding COI the three tele-presences have an emotional perspective:

Themelis,C.(2014). Synchronous Video Communication for Distance Education: the educators’ perspective. Open Praxis, vol. 6 issue 3, July–September 2014, pp. 00–00 (ISSN 2304-070X). http://www.openpraxis.org/index.php/OpenPraxis/article/viewFile/150/123

who are the figures that play a role in the formation of the community?

It is truly a nice and helpful piece of information. I am glad that you simply shared this helpful info with us. And also thank you

thank you for sharing. where the inquiry model come from?