A major goal of net-based mass media is to customize the feed that is delivered to each viewer received a unique screen that matches their interest and more importantly their likelihood of purchasing some product or viewing some paid for message. This phenomenon was labeled as “filter bubble” by author Eli Pariser – meaning that certain results are filtered out creating a bubble of unawareness that surrounds each of us.

I remember my first vivid encounter with these covert filters when I was building a web site some years ago for the Westwood Unitarian Congregation. I was flattered when I noticed that a Google Search started turning my site up not only on the first page of search returns but increasingly in first or second place. I naively imagined that our site was becoming the most popular Unitarian destination in Canada. Sadly, I came to realize that this top end response was only being enjoyed by myself. Google searches filters had determined that I really liked that site (based on my subsequent keystrokes) and thus presented a filtered result of searches for Canada and Unitarian. Obviously the search engine had established a personal profile for me and was feeding me what it thought would be of most interest to me.

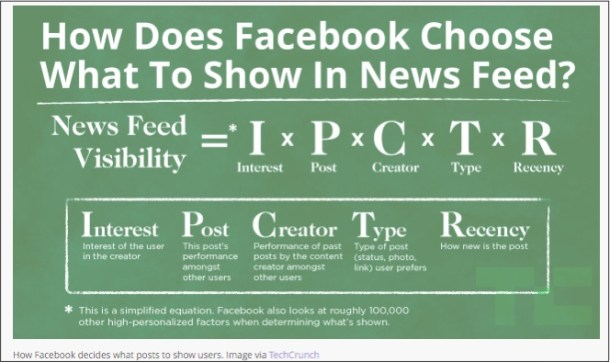

More recently, the use of filters by Facebook to provide customized news feeds to individual users has raised both technical and ethical issues. The diagram below by TechCrunch demonstrates a small part of the filter system used by Facebook and other media outlets.

One can argue the value of these filters (how many ads for women’s perfume do I really need or want to see?) but they come a cost of reducing the variability that exists throughout societies and may leave us blind to ideas or events that we may have both interest and expertise.

This is no more critical a problem than in academic research. When doing any quality work and especially that associated with PhD study, the candidate as an obligation to purview all of the relevant literature. Long gone are the days when this could be accomplished by a few afternoons in the periodical section of the library. Today this means searching through the academic databases – extracting and reading everything relevant to the topic. This can be done using proprietary search indexes such as Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) or rival product Scopius, however I have long argued that these indexes discriminate against both new Journals in the discipline and especially those that are Open Access.

Google Scholar is my first choice for such searches for a number of reasons. First it providing broader coverage than its competitors that includes documents from the grey literature (conference papers, reports, white papers etc.). Second it indexes far more journals in the educational discipline than either Scopius or SSCI. Third, empirical tests have shown that the results are not significantly different when using any of these indexes (see Harzing, A.-W. K., & Van der Wal, R. (2008). Google Scholar as a new source for citation analysis. Ethics in science and environmental politics, 8(1), 61-73.) Finally, and critically importance for scholars in developing countries and those non affiliated with a relatively rich university, is that access to Google Scholar search is free of charge (unlike SSCI).

So tying these two threads together (choice of search engine and covert filtering), leads to an obvious and important question. Does Google Scholar filter results? Or can one expect different search results to arise when different scholars with different experiences, interests and use profiles?

I was pleased to hear that has question has been addressed and the results did not displease me (ie they made it past my filtering to be presented to you, in this blog!!). The study:

Yu, K., Mustapha, N., & Oozeer, N. (2016). Google Scholar’s Filter Bubble: An Inflated Actuality? Research 2.0 and the Impact of Digital Technologies on Scholarly Inquiry, 211.

compared Google Scholar research results using variety of default and advanced settings (see abstarct below) and it concluded “that the filter bubble phenomenon does not warrant concern.” Unfortunately the chapter and the book are not open access however the main points can be seen from the Google Book abstract or the publishers preview.

Thus, my faith in and appreciation for the service provided by Google Scholar has increased.

ABSTRACT:

This chapter investigates the allegation that popular online search engine Google applies algorithms to personalise search results therefore yielding different results for the exact same search terms. It specifically examines whether the same alleged filter bubble applies to Google’s academic product: Google Scholar. It reports the results from an exploratory experiment of nine keywords carried out for this purpose, varying variables such as disciplines (Natural Science, Social Science and Humanities), geographic locations (north/south), and levels (senior/junior researchers). It also reports a short survey on academic search behaviour. The finding suggests that while Google Scholar, together with Google, has emerged as THE dominant search engine among the participants of this study, the alleged filter bubble is only mildly observable. The Jaccard similarity of search results for all nine keywords is strikingly high, with only one keyword that exhibits a localized bubble at 95% level. This chapter therefore concludes that the filter bubble phenomenon does not warrant concern.

Hi! Thanks for this interesting post.

Anurag Acharya, Google Scholar’s Chief Engineer, declared last year that they don’t change results based on user profiles. Everyone gets the same results for the same queries. They only change the order in which they appear depending on your preferred language (if your interface is set to Spanish, you get results in Spanish first, and so on). The full text links also change depending on the subscriptions of the institution from which you’re accessing Google Scholar

https://youtu.be/S-f9MjQjLsk?t=53m

See my comment on https://medium.com/advice-and-help-in-authoring-a-phd-or-non-fiction/doing-a-quick-literature-review-f94700f947ce#.aklnn8geb